Writer Elizabeth Wurtzel died yesterday at age 52 of leptomeningeal disease — a complication of metastatic breast cancer that had spread to the fluid around the brain and spinal cord.

Elizabeth Wurtzel, New Year’s Eve, 2010. Photo by Wendy Brandes.

I met Elizabeth on Wednesday, May 27, 2009. I know the exact date because we were at a black-tie dinner at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. At the end of the evening, I was too shy to approach the instantly recognizable author of Prozac Nation by myself, but I couldn’t pass up the opportunity either. So I grabbed MrB by the back of his tuxedo jacket; stage-whispered, “Tell her you’re an important journalist”; and propelled him over to her. I peeked out from behind him once the ice was broken, and she and I struck up an unlikely, on-and-off-and-on friendship independent of MrB.

Elizabeth was intelligent, funny, generous, and loyal, but she was also provocative, boastful, and contrarian. She was miserable about minor life issues and stoic about major ones. “I have always been the most impossible person ever,” she wrote in a 2018 essay in the Guardian. That was the piece in which she announced that the BRCA-gene-linked breast cancer she’d been diagnosed with in 2015 had advanced to Stage 4. She wrote:

“I hate it when people say that they are sorry about my cancer. Really? Have they met me? I am not someone that you feel sorry for.”

She went on to say:

“I love to argue. I am in it for the headache. I don’t need you to be on my side – I’m on my side. Everyone is entitled to my opinion. I love being controversial, because that’s the closest you get to everyone agreeing with you – the other choice is no one is paying attention.”

In contrast, debate isn’t my sport. I think the devil has enough advocates. When I express a strong point of view, it’s because I believe in it. I might be persuaded to change my mind, but I never take a position merely to get a reaction. The fact that I stayed in touch with Elizabeth (Lizzie to her other friends) for 10 years is a tribute to her charisma and persistence, because there were times I was ready to pull out my hair after an evening with her. She was unpredictable. She could be silly and fun in a show-off-y way: When former news anchor Tom Brokaw invited questions after a documentary screening about “American characters,” she was the first person to put up her hand, only to ask, “Is the farmer single?” More frequent — and frustrating to me — were the occasions where I’d finally be convinced by an aspect of a passionate argument she made on, say, the criminal-justice system, only for her to immediately switch sides and debate her previous stance with herself.

But Elizabeth was also an animal lover who sent me white roses when Purrkoy, my four-year-old cat, died of a stroke. She championed my jewelry line to everyone she introduced me to in person — as well as on social media — and liked to request special projects. I’d stopped making my Cleopatra earrings in silver, for instance, but I made one more pair for her, which she then wore every time she saw me — no exceptions. “You don’t have to wear those every time I see you,” I’d say. “I wear them every day,” she’d claim. “Take a picture for Instagram.”

Two years ago, we were drinking wine at her chockablock apartment — in the company of her petite black cat Arabella and her large, unfriendly emotional support dog Alistair — when she calmly told me she had a new writing project because she’d found out, at age 50, that the man she thought was her biological father was not. “I’ll call it ‘Bastard’,” she said. I tried to absorb the details of this life-upending discovery without interrupting my usual negotiations with Alistair, who would growl at me fiercely in unnecessary defense of his besotted owner before deigning to sit next to me on the couch. Yet that revelatory evening rates as ho-hum next to a chaotic outing years earlier during which Elizabeth gave me a complicated explanation of why she needed to use MY credit card to pay HER cable bill right at that moment — in the restaurant, over dinner, in front of a slack-jawed friend of mine whom she’d never met before. She did pay me back in cash on the spot, as promised. Later, she provided a more concise reason for her predicament: Even after you get sober and graduate from Yale Law School, an addiction to Ritalin and cocaine has a long-lasting effect on one’s finances, which includes one’s relationship (or lack thereof) with the IRS.

Her drug history was no secret. I’d read her 2001 book More, Now, Again, which is subtitled “A Memoir of Addiction.” She’d gotten me to custom-make her a silver version of my 18K gold lapis lazuli Nefertiti ring by reminding me of Chapter 21, in which she’d lost a beloved lapis ring in Iceland, where she’d wound up unexpectedly after taking some very strong heroin in Amsterdam.

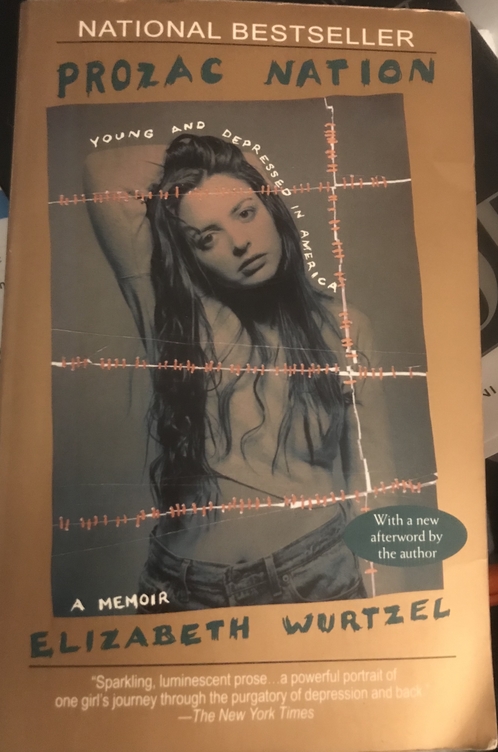

More, Now, Again was Elizabeth’s second memoir, after 1994’s Prozac Nation. (In between was 1998’s book of essays, Bitch: In Praise of Difficult Women.) Prozac Nation told the story of her 10-year battle with severe depression that began when she was a pre-teen and lasted until she was a Harvard undergrad. That depression was alleviated only after she became one of the earliest users of the antidepressant Prozac. Prozac Nation was intensely personal and specific to Elizabeth’s struggles, but also potentially relevant and reassuring to anyone her age who had also suffered from depression. It was The Bell Jar for a new generation, and Elizabeth wanted to call it I Hate Myself and Want to Die.

Instead, an editor with a flair for marketing pounced on “Prozac Nation,” the title of Elizabeth’s epilogue, which dealt more broadly with how Prozac and other new drugs in the same family were so successful at treating depression — relative to past options — that the mental illness had become both mainstreamed and trivialized. As Elizabeth wrote:

“It seemed that suddenly, some time in 1990, I ceased to be this freakishly depressed person who had scared the hell out of people for most of my life with my mood swings and tantrums and crying spells, and I instead became downright trendy.”

With a book title that implied a treatise on society at large (helped by the addition of the subtitle “Young and Depressed in America”) and a grunge-style but alluring author cover photo …

… Elizabeth was turned into a poster child for depression as well as a pop-culture phenomenon that, like the drug of the title, was both everywhere and misinterpreted. People who didn’t read the book assumed (and still do) that it is one long advertisement for medication, even though Prozac isn’t mentioned until page 296 of the a 331-page book and doesn’t become an effective treatment for Elizabeth until page 329. And, in the epilogue, Elizabeth pointed out that Prozac wasn’t a cure-all or a personality-altering “happy pill”:

“… after six years on Prozac, I know that it is not the end but the beginning. Mental health is so much more complicated than any pill that any mortal could invent.”

As for the people who did read the book because they were paid to — critics — many of them were outraged that a sad, attractive, white, Harvard girl could be considered “the voice of a generation,” no matter how unstable her home life had been. A Chicago Tribune interview with her in 1995 listed some of the angriest responses, including:

“(The book) is one long whine, a tedious tome, a depresso-manifesto, a celebration of self-pity and thinly disguised narcissism. I am. Read me. Feel me. Heal me. Buy me.” — Jim Sullivan in the Boston Globe

“Wurtzel’s memoir of what it was like to grow up smart, sensitive, talented and miserable would be moving in its specificity were it not so prattling and smug.” — Mark Harris, Entertainment Weekly

But within Elizabeth’s actual text, she never presented herself as the voice of a generation. She was brutally honest about her personal despair and unusually willing to lay bare her worst, meanest, most embarrassing, and most selfish thoughts and actions — the kind people like me might never admit to their therapists or even to themselves. As she told the Tribune:

“I set out to write a book which was true to being depressed, which is extremely self-involved. I really wanted it to feel as bad as depression feels …”

The only critic I’ve read who understood that Elizabeth had any self-awareness was Michiko Kakutani of the New York Times, who wrote, “Ms. Wurtzel herself is hyperaware of the narcissistic nature of her problems, and her willingness to expose herself — narcissism and all — ultimately wins the reader over.”

I re-read Prozac Nation this weekend, after I found out Elizabeth had taken a sudden and final turn for the worse. Treatment had kept the cancer corralled in what she called “a spot in the bone” for a long stretch, during which she carried on a normal social life. The last time I saw her, in the summer, we went to see the band Bikini Kill, though she got more pleasure from a chilly afternoon when we drank a couple of margaritas before her radiation appointment. She was thrilled that the medical staff told her she was the first person to show up in a mild state of inebriation, and she gleefully deemed me a corrupting influence. After reading the book again, I am rather impressed with that designation, because even briefly playing the role of the bad girl in Elizabeth’s life is a feat I wouldn’t have dreamed possible. But mostly I was struck by how terrible and intractable her depression became because she had internalized all the shame, criticism, and pressure that unsympathetic readers would later hurl at her. In the book, she remembered a conversation with her therapist like this:

“This is going to sound dumb,” I began, far too aware that everything I said was so trite, “but, the thing is, I really don’t feel like I have a right to be so miserable. I know we can look back and say my father neglected me, my mother smothered me, I was perpetually in an environment that was incoherent to me, but –” But what? What other excuses do you need? I wasn’t feeling gross enough to mention Bergen-Belsen, cancer, cystic fibrosis, and all the other REAL reasons to be sorrowful. “But a lot of people have hard childhoods, I continued, “much harder than mine, and they grow up and get on with it.”

“A lot of them don’t.”

“I don’t care about the ones who don’t. I think I should be among those who do. I’ve been so lucky in so many ways, had so many compensations –” It made me sick listening to myself. How many times and to how many therapists had I made this speech? When would I stop wondering what right — what NERVE –I had to be depressed?

That passage — and others like it — give Prozac Nation an enduring, underestimated value. If only I’d been able to absorb the lesson when the book came out 25 years ago, not long after I began consistent treatment for my own depression! Instead, I made minimal progress for over a decade because I couldn’t escape the self-loathing spiral that starts with “other people have it worse,” which Elizabeth described so vividly. Elizabeth herself was an example of “worse” for me. If she was the epitome of privilege, as critics said so loudly and so often and so angrily, what was I? Unlike her, I’d had a stable home life; my parents have now been married more than 50 years. I was never tempted by drugs. I never needed to be carried kicking and screaming to a medical facility. I figured I really had nothing to complain about. Luckily, I’m a creature of habit and I kept turning up at therapy appointments until it dawned on me that it didn’t matter if I was “entitled to” or “deserving of” depression — or any other illness, whether mental or physical. Whatever it is, if you’ve got it, you’ve got it, and the only way forward is to accept the reality and get the best possible treatment.

Once I had that epiphany, it was easy to see the impact of the shame spiral on practically everyone who has confided in me about their depression and/or anxiety. Everyone thinks they “should” be better, they “should” snap out of it, they “should” do this or that. There are so many “shoulds”! I say the only thing you “should” do is acknowledge that you didn’t ask for this condition but you’re allowed to get help anyway. (Here’s a cheat code: If you absolutely can’t bear to do something good for yourself, tell yourself it will benefit the other people in your life.)

I hope that new readers will draw that message from Prozac Nation now that the book is free from the scathing contemporaneous criticism of the 1990s, and obituary writers have been forced to reckon with Elizabeth’s influence on publishing and popular culture.

I hope they have unlikely optimism, as Elizabeth did when she signed my old copy of Prozac Nation this way, after a long discussion of our lack of boundaries.

I hope they realize the journey — the fight — is worth it. As Elizabeth wrote in the Guardian:

“Do you know what I’m scared of? Nothing.

Cancer just suits me.

I am good in a fight. This one goes on for the rest of my life. But I have been fighting with myself in one way or another all along. I am used to it. I can’t think of a time when my mind or my body was not out to get me. I am at ease with this discomfort. I am a ballerina doing a pirouette with perfect turnout in toe shoes, and it does not even hurt any more. I am elated. I love spinning this way. I would not have it otherwise.”

I hope they realize it’s never too late to get better … but it’s never too soon either.

The years do fly.

My god, Wendy, this is amazing.

👍👍👍 I have never read her books and now I am curious. I somehow managed to not even notice them much in life.

Sorry to hear she passed away.

Oh, now she’s going to come haunt you! LOL! Elizabeth hated to be unnoticed. You better rectify that before you end up with a book-oriented poltergeist 😉

Why you don’t write obits for the NY Times is beyond me. Another amazing piece – all the more fascinating because of your friendship with EW. She was undoubtedly a complicated person and I love that you don’t sugar coat that here – even as your fondness for her is evident.

Thank you, Kristin! While I was writing this I was thinking “Eek, this is too personal for me!” … which made me appreciate Elizabeth’s openness even more. She held back nothing!

I’ve been waiting for your take on this. I liked her writing a lot, and her openness about her mental health helped me and a lot of other people. I’m sorry that you lost a friend. She made a real contribution and I hope she’s at peace now.

It’s so good to hear that her work was helpful to you. She would be so pleased.

Prozac Nation was my companion during the lowest of my low. I am devastated. On the other hand, that was beautiful and I’m happy that she was your friend.

Thank you for commenting — I love hearing from people who were helped by her writing. I feel like the critics never acknowledged that aspect.