In honor of World AIDS Day, I’m going to say a few things about the The AIDS Memorial Instagram account — one of the most important and moving accounts on the ‘Gram, in my opinion.

CLICK TO VISIT THE AIDS MEMORIAL ON INSTAGRAM.

I’ve been meaning to write about this account since last year, when I exchanged a couple of messages with the founder of the account, who I was surprised to learn lives in Scotland. I had the idea of doing a story for the Huffington Post but I procrastinated, in part because it’s a heavy topic, but mostly because I kept thinking, “What if I don’t do this story justice?”

I feel strange writing about how devastated I felt as the AIDS epidemic raged in 1980s and 1990s, because, as sad as I was, I was on the outside of the tragedy, looking in. I was lucky enough not to lose anyone close to me. But I know many people who lost a family member; a partner; or dozens — sometimes even hundreds — of family members, lovers, friends, colleagues, and acquaintances. The distress I felt and still feel is nothing at all compared to their pain.

Still, the disease swept away a vast portion of the people I idolized from afar. In the early ’80s, when I first noticed the ever-increasing number of obituaries for very young men and then read about “gay-related immunodeficiency” — as AIDS was originally identified — I was a high-school student feeling out of place in a small town in New Jersey. My No. 1 goal was to move to New York and be surrounded by fabulous avant-garde people. If those people happened to be gay men, so much the better. With gay guys, I could have fun with no worries about ulterior motives on their part, plus I had so much more in common with them than with straight guys. Who else would share my taste in fashion, film, music, theater, and art? So I would take the train to Manhattan with my one gay friend and one bi friend from school and we’d visit the Oscar Wilde Memorial on Christopher Street. I would buy publications like the Village Voice, the East Village Eye, and Details magazine, which I would read and re-read at home. I knew all of the people who made New York a scene — just not in real life, yet.

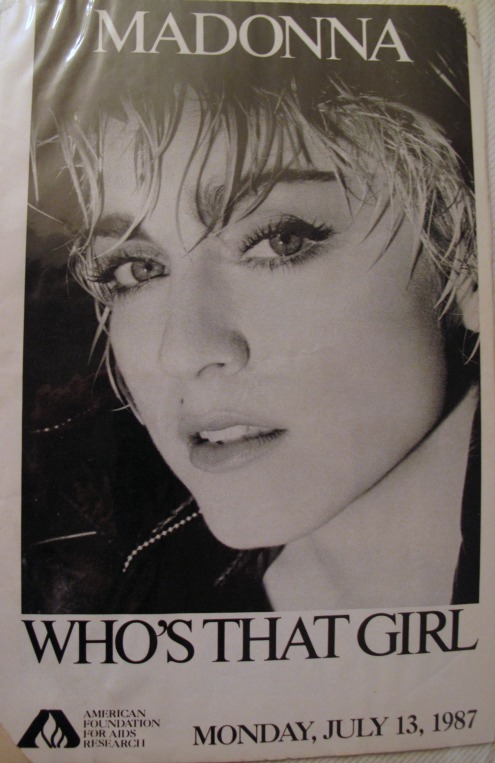

And then, the men started to disappear. A lot of times, obituaries listed another cause because the stigma of AIDS was so terrible — remember, in 1987, Princess Diana generated shocked headlines for visiting the U.K.’s first AIDS ward and shaking hands without wearing gloves — but it was easy to read between the lines as the leading lights of creative industries were wiped out. In fashion alone there was Perry Ellis, dead at age 46; Willi Smith, at 39; Isaia Rankin, 35; Angel Estrada, 31; Carmelo Pomodoro, 37; Clovis Ruffin, 46; Patrick Kelly, 35, Chester Weinberg, 54; Halston, 57; Franco Moschino, 44. But, as this article by Kam Dhillon points out:

“It wasn’t just designers but showroom assistants, stylists, photographers, creative directors, window dressers — an entire generation of creativity, completely decimated.”

“There’s a finite fund of talent in any generation,” said fashion writer Holly Brubach to People magazine in 1990. “There is an assumption that if a great designer dies, someone else will step in to replace him. But if AIDS keeps up as it has, we are going to be living in impoverished times. Each time a person of great talent dies, the landscape gets a little more drab.”

Of course, the decimation wasn’t limited to the fashion world. This article from Vanity Fair covered the impact of AIDS in the 1980s on the beauty world, movies, dance, music, art, theater, and interior design — and so many of those in New York. Just today, stylist Bill Mullen, a survivor of the era, mused on Instagram about the long-term effects of all the deaths on the city: “Sometimes when everyone complains about how bad New York is now with no Studio 54 or Mudd Club or whatever and fashion in a shambles and the art world only about money and dead magazines and so little style or substance or quality left, I think it wouldn’t be like this if those beautiful people were still here.”

For a visual representation of the impact of AIDS on one small group, you can see the famous photo that Eric Luse of the San Francisco Chronicle took of the San Francisco Gay Men’s Chorus in 1993. Seven men in white shirts are surrounded by men dressed in black with their backs to the camera. The men in white were the only survivors of the original chorus; the men in black represent the ones lost to AIDS.

CLICK HERE TO SEE THE ERIC LUSE PHOTO.

Three years later, Luse re-released the photo but amended the caption to say that if he retook it, all the men would be in black, because the obituary list was now 47 names longer than the chorus roster. (Last year, on its website, the chorus said last year that it had lost over 300 members to HIV/AIDS since 1981.)

Five years ago, Simon Doonan of Barneys wrote about a friend named Jeffrey Herman, a “model turned photographer who had just begun to receive some recognition for his pictures” in the ’80s. During Herman’s final days, he said:

“This is the end. We were all headed toward oblivion. Nobody will remember us. We will evaporate. We are dust. We are the lost generation.”

As I’ve written before, remembering people and their stories is important to me and that’s why — and I’m getting back to my original point here — I appreciate the crowdsourced AIDS Memorial Instagram account so much. Kate Kellaway did what I failed to do and wrote a proper story about it for the Guardian this November. The Scottish account owner, who started the feed in April 2016, is identified only as Stuart. (He “prefers to keep himself – and his surname – out of the story,” Kellaway wrote.) As for his motive: “History does not record itself,” he said. Anyone who wants to memorialize someone lost to AIDS can email or message Stuart to share the story. “If you don’t have a photo of your loved one, he’ll help you find one,” Kellaway wrote. “If no image exists, an illustration by artist Justin Teodoro will be used instead.” The photo issue is something that jumped out at me about the memorial account early on. We’re so spoiled by endless digital photos now; we can keep a thousand photos of our sleeping cat on our phone. In the 1980s, we had real film with 24 or 36 exposures per roll, plus the expense of developing photos and the need to find a place to keep anything that was printed. It makes me emotional to see an image of a creased or faded photo on The AIDS Memorial feed and learn that that’s one of the few pictures — or even the only one –that exists of a loved one.

Another thing that stands out to me is the many women from the fashion world who comment and remember and pay tribute. The severe trauma of the men who lost practically everyone around them (while fearing for their own health whether or not they’d tested positive for HIV) was long known to me; this San Francisco Chronicle coverage of long-term survivors is good if you’re not familiar with the issue. But, to be honest, I hadn’t considered how many women in fashion-adjacent jobs whose closest colleagues were gay men also have AIDS-related PTSD. It hit me a few years ago when I was looking through my hair stylist friend Julie’s old photo albums and she was pointing out people who were gone, and I see more evidence of it on The AIDS Memorial regularly. Another group of survivors who sometimes are overlooked are the children of people who died of AIDS. There is a separate Instagram account called The Recollectors that is focused on the stories of those lost parents — I found it when The AIDS Memorial reposted some of those photos — that is worth following as well.

I’m not sure how often anything on Instagram can be deemed heroic, but this project launched by Stuart from Scotland deserves that distinction. Thirty-something years after photographer Jeffrey Herman, on his deathbed, said, “No one will remember us,” a repository for memories thrives.

Thank you for pointing me to this!